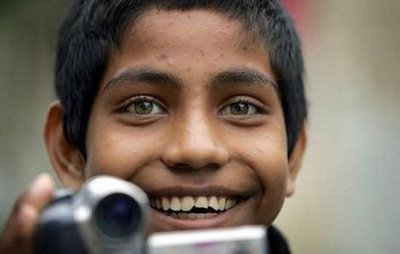

VIA: Middle East OnlinePoverty-stricken parents encourage trafficking of their children from Yemen to Saudi Arabia to work as beggars.By Christian Chaise - SANAA

VIA: Middle East OnlinePoverty-stricken parents encourage trafficking of their children from Yemen to Saudi Arabia to work as beggars.By Christian Chaise - SANAA

Misery in Yemen continues to encourage child trafficking into Saudi Arabia, with widespread cases of parents paying smugglers to take on their offspring to work as beggars on the streets of the oil-rich neighbour.

Thousands of children, as young as seven and including girls, continue to be entrusted by their parents to traffickers who help the youngsters cross the desert borders illegally into Saudi Arabia, UN officials said. The children, who mostly come from large and poor families, sweat to earn money through small, menial jobs or most often by begging on the streets. Thousands of them are regularly caught by Saudi police and sent back home.

Trafficking mostly feeds on extreme poverty in northern Yemen, particularly in the province of Hajjar which is close to the Saudi border.

"Now

families are paying smugglers to take their children to Saudi Arabia," Ramesh M. Shrestha, a representative of the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), said. "We've heard of agreements between traffickers and parents with government officials as witnesses to make sure the traffickers will pay," he said. He said "

each kid is sending 200 to 500 dollars to their family each month," in a country where annual revenues per capita are just a bit more than 500 dollars. The alarming situation has prompted UNICEF and the Yemeni ministry of social affairs to organise the country's first conference on the subject in Sanaa in January. It was the first time that Yemeni authorities officially admitted the problem, most probably because it constituted negative publicity for the country.

Prime Minister Abdel Kader Bajammal however still insists that trafficking of children - words that authorities do not like to use to refer to the problem - involved only "cases, not (a) big quantity." Shrestha also said that the situation was even more complicated by the fact that many children were also illegally brought into Saudi Arabia from Yemen by their own parents.

In the first quarter of 2004, more than

150,000 Yemenis, including 9,815 children, were expelled from Saudi Arabia. The number of those who were victims of trafficking however is not known.

Most of the Yemeni children smuggled into Saudi Arabia were boys aged between 10 and 16, said Shrestha.

The Yemeni Centre for Social and Labour Studies said in a study that "the child trafficking problem is one which, though it did not originate at that specific time and might be very old, became significant as a result of the Gulf crisis (war) of 1990-91." "Due to the opposition of the Yemeni government to the Saudi cooperation with America and the allies against the Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein, Saudi Arabia repatriated many Yemeni migrant workers and since then, there has been greater difficulty in legally obtaining employment in Saudi Arabia," it said.

Shrestha said that another main hurdle obstructing efforts to curb the problem is that

"in Yemeni criminal law, there is no mention of trafficking of human beings. So it is not legal or illegal." "Even when traffickers are caught, they are released, because it is not illegal," he said, calling for legal amendments. Shrestha said that another main problem that encourages the trafficking of children is the miserable state of the educational system.

School may be mandatory in Yemen, but only 80 percent of children actually enroll. With half of the 20 million population under 18 years old, Yemen only has 13,000 schools, among them 800 for girls.

"I am really not so sure what is feasible in the short term and in the long term," added Shrestha.

I would like to acknowledge the philanthropic contribution of Fuad Musa. After my speech at 2006 Badr Conference Fuad approached me and on behalf of his company, FuFu Products, he donated 40 beautiful mugs with the simple condition that all the proceeds go to the orphans and vulnerable children I work with in Ethiopia. Due to his altruism and the compassion of the Ethiopian Muslim community, I was able to raise enough funds to support two of the kids in Project FACE for a year.

I would like to acknowledge the philanthropic contribution of Fuad Musa. After my speech at 2006 Badr Conference Fuad approached me and on behalf of his company, FuFu Products, he donated 40 beautiful mugs with the simple condition that all the proceeds go to the orphans and vulnerable children I work with in Ethiopia. Due to his altruism and the compassion of the Ethiopian Muslim community, I was able to raise enough funds to support two of the kids in Project FACE for a year.